For part 1 of the 2021 Chase-cation blog, please click here.

May 25th (down day # 2) in Omaha

Our second down day in Omaha was spent working, watching my cousin’s graduation, and a ton of forecasting. The next day looked like a possible severe weather outbreak, with a good looking setup for isolated, powerful tornadic supercells on the dryline from the northern Texas Panhandle to southwest Nebraska, and potentially as far northeast as Lincoln along the warm front, depending on how far north the warm front would make it the next day. There was some uncertainty as to how far south sustained convective initiation (CI) would occur, due to capping issues on the dryline, but instability and wind profiles otherwise strongly favored tornadic supercells. For the 27th, there looked to be messy targets in northern Oklahoma and in the Texas Panhandle, while the 28th looked like a really good upslope play in the Permian Basin in southeast New Mexico or southwest Texas. We were also planning on staying the night of the 26th in Enid, OK, which pulled my ideal target for the 26th south. Part of the challenge of a chase-cation is forecasting several days in advance, and because of the vastness of the Great Plains, the human need for sleep, and the lack of a Tardis, we had to pick our target areas accordingly.

May 26th Kansas Supercells and Tornado (Omaha, NE --> Leoville, KS --> Liebenthal, KS --> Scott City, KS --> Enid, OK)

At about 8 a.m., we departed Omaha westbound on I-80, a series of podcasts in tow, for what looked like a promising but long day of chasing. After occasional data checks on the westward journey, the target still seemed to be somewhere between Dodge City and Leoti/Scott City, KS in the late afternoon or early evening. We crossed into the rolling hills of northern Kansas late in the morning, and CI began early to our west, near Goodland and Colby, along the northward lifting warm front. Pictures of a gorgeous, bell shaped updraft with one of the cells along the warm front streamed in on Twitter; a supercell was riding to the northeast along the warm front, taking advantage of an environment with plenty of streamwise vorticity and moderate capping to produce beautiful structure. After a gas stop in Norton, we continued west on K-383, hoping to see this early supercell before it weakened north of the warm front. The supercell was moving slowly to the east northeast, and with K-383 aligned from Norton to the west southwest, though with plenty of south road options, this seemed like an easy intercept. Then, roadwork happened. We were stopped at a flag-man. Minutes before, the hardest part about getting into position for the storm was finding a spot where we could get Immaculate Conception Church near Leoville in the foreground for pictures of supercell structure. Now, with severe thunderstorm warnings still calling for tennis ball size hail along K-383, I worried aloud that I’d navigated us into a trap while we waited over 10 minutes for a pilot car. Finally, the pilot came. We crept across northwest Kansas at about 30 mph behind the pilot car, hardly an ideal speed when trying to catch a supercell, but it beat waiting helplessly and hoping to not get hailed on.

When we neared the tiny town of Leoville, the beautiful updraft of the supercell unveiled itself. The updraft was vertically divided into pancake-like stacks, though with an upward thrust in the center, indicative of where dynamically-forced ascent in mesocyclone was acting on more statically stable air in the boundary layer.

|

| Early glimpse of the Leoville supercell, between Norton and Leoville, KS |

We went just south of Leoville and set up for pictures with a dirt road leading towards the updraft, and the red brick, double-spired Immaculate Conception Catholic Church to our north. As seen below, the updraft evolved into three, sometimes four, stacked plates, with blue and gray coloring, which gave the illusion of rolling ocean waves. The storm, as it died while crossing north of the warm front, exuded the overwhelming beauty of what a supercell updraft can look like in an environment rich in streamwise vorticity, but with just the right amount of convective inhibition and mid-level dryness to show a sculpted updraft. For an approximated proximity sounding via the RAP model, please click here (courtesy of the US Tornadoes Case Archive created by Cameron Nixon).

|

| Leoville supercell rapidly weakening |

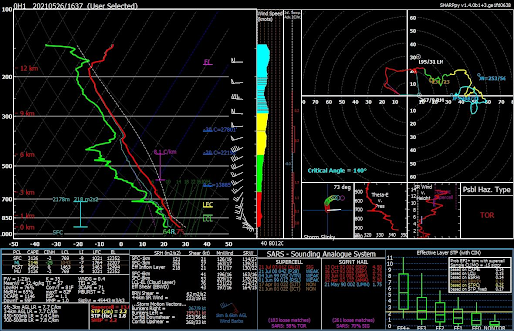

I wondered if we were the only chasers watching the Leoville cell die (we hadn’t seen anyone else who was obviously a storm chaser, which was a welcome surprise as far as avoiding convergence). A quick check of my phone gave us the answer as to why: most people had bailed south and east on I-70, as a cluster of strong updrafts had formed along the warm front close to Hays in a very favorable environment for tornadic supercells (in an area which most CAMs that I’d looked at did not depict CI in). My friend Jason texted me a picture of a 17z sounding launched from near WaKeeney by the Texas A&M crew, which indicated how good of an environment the new convection was likely in (see WaKeeney special sounding here):

| ||

| Special 17 UTC sounding near WaKeeney, KS, courtesy of Texas A&M University group. |

We realized that we had time to get to the WaKeeney/Hays cells without taking ourselves out of position for the outbreak of powerful supercells we were still expecting in southwest and west-central Kansas late in the afternoon. After a quick rest area stop near Quinter, we arrived to the northwest of a strong supercell, which was somewhat high precipitation (HP). Due to the storm’s very slow eastward movement, we exited I-70 and stair-stepped our way southeast to get to the south of the updraft, monitoring local radio stations for warning information while we went in and out of cell service. The low-level hodograph, with its very concave shape and strong storm-relative flow, concerned me, due to the apparent potential for deviant storm motion. While we stair-stepped on county and state highways to the southeast, across the central Kansas prairie, I got a bit concerned about our intercept strategy. We needed to monitor the radar, watch what was going on in the sky, and plan escape routes. The technology I had available (a cell phone and a AAA Kansas/Missouri map) didn’t allow me to easily keep track of where we were with respect to the escape routes while doing the other tasks. My dad identified the secondary escape route we’d picked out as we approached the southern side of the supercell, just to the east of Liebenthal, and helped us to maintain situational awareness while we moved east of Liebenthal.

To our left, the supercell seemed to be occluded and reorganizing

its low-level structure, appearing as a mass of gray precipitation set above

and behind ridges of brown and yellow fields. While I buried my face in

RadarScope, my dad and uncle (who was driving) noticed an odd, white, tubular

shape, shrouded in the rain to our distant left. Alertly, my dad asked, ‘I know

I’m not the meteorologist in the car, but is … that a tornado?’. I immediately

dismissed the suggestion, not thinking that there could be a tornado that far

rearward of the occluded low-level mesocyclone. Then I looked left. I was

wrong. It was our first Kansas tornado. In retrospect, given the strong storm-relative flow in the very concave low-level hodograph, the deviant leftward displacement of the tornado made sense.

|

| Poor contrast, but I didn't care, since it was my first Kansas tornado. |

By the time that we made it to our southward escape route, this elephant trunk tornado had dissipated. A new cell was developing on the southward flank of the previously tornadic supercell, as evidenced by a stout updraft base and widely scattered large hail falling diagonally around us.

|

| New supercell near Liebenthal, with hail falling diagonally around us. |

This new supercell barely moved as the low-level mesocyclone organized while it merged into the old storm’s forward flank. Briefly, I worried that the storm had taken a turn towards us and that we needed to bail south, east, or west (thankfully we had multiple escape routes open), but realized in a minute or two that the storm was merely stationary. The storm structure improved and became somewhat photogenic, but when it approached 3 p.m., it became clear that if we wanted to head to our original target of southwest/western Kansas, we’d need to leave shortly. We admired and photographed the slowly morphing, beefy structure for a few more minutes, said our goodbyes, and went west.

|

| Inflow bands on second Liebenthal supercell |

|

| Inflow bands on second Liebenthal supercell |

|

| Getting ready to leave second Liebenthal supercell |

As we passed westward through a particularly rural section of central Kansas, several things occurred that made me optimistic for our chances of seeing visually appealing tornadic supercells later: 1) The low-level shear seemed to already be as strong as models suggested it would be, as evidenced by a horseshoe vortex seen out of our port side, 2) CI had taken place near Leoti along the dryline, and 3) a PDS tornado watch from SPC, the reasoning (in the text discussion) of which matched my thinking for what was going to happen later.

|

| Horseshoe vortex, somewhere near Utica, KS |

We made it to Scott City (also a badly needed gas stop after a rural COOP gas pump malfunctioned near Utica) and followed the initial cells north. Contrary to expectations, these storms did not strengthen, but instead were raggedy low-precipitation storms (until they reached southwest Nebraska, where they would produce photogenic tornadoes near the warm front). If we weren’t targeting the far southern High Plains a couple days later and planning a stay in Enid that evening, we’d have considered venturing back into Nebraska. But we were tired and hungry, so we went back south from near Colby to Scott City for a quick bite of Subway and to hedge towards Enid.

|

| Low contrast LP storm, somewhere between Scott City and I-70 |

While at Subway, new convective initiation occurred to our south, near Dodge City. If this new updraft could sustain itself away from the dryline in the presence of what seemed to be a stronger-than-forecast cap, it would be in a very favorable environment for powerful tornadic supercells during the evening. Since we needed to go to Enid, we bolted south out of Scott City, with a churning updraft to our south. Just as soon as I thought we were going to get another supercell to chase, however, the updraft split, and both the right and left splits shriveled during our approach to Dodge City.

|

| Dodge City supercell beginning to split |

|

| Dodge City cells starting to weaken |

|

| Goodbye, storm. |

We passed through Dodge City just before sunset and set our route to Enid, passing by groups of dejected storm chasers wallowing on the roadside. On the bright side, this was the first time that I had been to Dodge City in roughly 10 years, and no disasters happened this time. On my previous two experiences there, both doing meteorological field work (both incidentally on May 27 in 2011 and 2012), I destroyed a cell phone and got food poisoning, respectively (never eat fish in the High Plains!). A busted final leg of an otherwise successful day of storm chasing was much preferable to either of those, plus the dying thunderstorm near sunset provided very pretty scenery. We drove southeast into northwest Oklahoma, amid a vividly colored sunset. Shortly after midnight, we arrived in Enid.

May 27: Some messy storms, a distant LP, and tasty pizza at Texas Tech (Enid, OK --> Childress, TX --> Lubbock, TX)

When I awoke, I was groggy and had little idea where I wanted us to target. That’s about how the rest of the day went, too. Despite the favorable conditions for supercells in central and northern Oklahoma, they looked like they’d be mostly HP storms with limited tornado risk, with a good chance of high storm density and messy storm modes. A somewhat better chance for photogenic, isolated storms, appeared to exist in the southeast Texas Panhandle and Texas South Plains, particularly in the corridor from Childress to Matador. Capping along the dryline seemed to be strong enough that while there would likely be storm initiation in the late afternoon, it would probably be widely scattered. Deep-layer shear was sufficient for supercells, though low-level hodograph shapes left a lot to be desired for photogenic storm potential. Since an initial target of Childress would bring us closer to the more obvious target for the next day (the Lubbock-Hobbs-Artesia-Roswell corridor), we settled on going southwest to Texas.

Upon leaving late in the morning, CI was already beginning in northern Oklahoma. Several messy, HP supercells developed near us and moved to the east and southeast as we passed by Watonga and headed for Clinton and I-40. The storms in Oklahoma evaded my laughable attempts at forecasting on the road, which unfortunately left my sister-in-law a bit in the dark on when to head south (she and my nephew made it to Texas safely, thankfully!).

We turned south off of I-40 at the Erick/Sayre exit, and almost immediately lost cell service, which we wouldn’t get back until we were approaching Childress, TX from the north, over an hour later, hampering my ability to forecast. We stopped for gas in Childress, and despite plenty of time to observe the sky and check surface observations, satellite imagery, and model forecasts, I didn’t have much of a handle on what was going to happen. We slowly worked our way south out of Childress, and convective initiation took place to the west! However, the nascent storm was struggling with the cap, so we slowly adjusted to the west on a Texas farm road to hedge towards the fledgling updraft.

The physical geography of this part of Texas was new to all of us, and the speed limits in Texas were also foreign to us. The winding, hilly, and just re-paved farm road (with loose gravel topping the tarry asphalt) had a 70 mph limit, which seemed more appropriate for a Top Gear challenge than for everyday driving. We stopped to watch and wait for the distant storm after averaging about half of that speed. The landscape in this part of Texas also possessed a sparse beauty, with bony shrubs dotting hills that varied between gently rolling and rough and jagged. This landscape was reminiscent of Willa Cather’s descriptions of parts of New Mexico in her novel Death Comes to the Archbishop (which is a great read, by the way!).

We came to a fork between two farm roads after coming out of a slot canyon. One fork would put us in position to intercept the storm, while the other would go south towards Matador and Dickens. Cell service was in and out, but the weak and pulsing character of the storm we were waiting on, combined with surface convergence and towering cumulus on the dryline to the south, made the south fork a more appealing choice.

We arrived to Dickens, TX and saw sustained CI to our west. However, the shear didn’t allow anything particularly interesting, other than a textbook cell split, to happen with our storm, which we watched from a high vantage point just to the east of town. A local storm chaser chatted with us near a roadside shelter atop the hill we’d pulled off on. Rather than pursue one of these splits to the east of Dickens, we took the local’s advice that that region was inhospitable for storm chasing, and started west towards Lubbock instead.

|

| Storm near Dickens, TX, before it split |

|

| Sun rays coming in after the split provided a pleasant scene |

Meanwhile, back up north … an LP supercell was prowling southeast among the broken hills southwest of Childress. I wished that we hadn’t grown impatient and gone south, and while we were westbound to Lubbock for the night’s lodging, we briefly went north to try to see the LP supercell from the south. It was difficult to see any of the striations in the updraft structure from our distant, southwest vantage, but isolated LP storms are still pretty, even from afar.

|

| Weakening LP supercell from distant southwest, likely near Matador, TX |

Finally, in Lubbock, we continued our pizza-after-chasing tradition with a really good pie from One Guy from Italy across the street from Texas Tech’s campus (sadly, per Google reviews, the quality seems like it’s slipped since we went after a change in ownership).

Last Chase: New Mexico lives up to its Land of Enchantment nickname (Lubbock, TX --> Roswell, NM --> Hobbs, NM)

Our last morning before a storm chase started with a continental breakfast. Other groups of storm chasers, including student groups, were discussing target areas for the day in the hotel lobby. I got a bit lonely sitting by myself looking at observations and model data, and asked a group of students from Western Kentucky about their thoughts on the day’s setup. After we agreed on a general target of Artesia/Roswell area, they asked where I was from. As it turned out, one of the WKU students was about to start as a graduate student at UNL in the fall; we realized that we’d be coworkers at the drought center a few months later (the meteorology community is quite small!).

Back to weather, the setup looked good for upslope supercells in southeast New Mexico. A cold front had dived south through the southern High Plains overnight. In the post-front regime, upslope flow was forecast to transport upper 40s to low 50s dewpoints towards the Sacramento Mountains in southern New Mexico. With sufficient low level and deep layer shear available for supercells, as well as decent hodograph curvature in the late afternoon and evening (see RAP forecast sounding below), there appeared to be potential for photogenic, high based supercells to move southeast out of the Sacramento Mountains into the Permian Basin.

|

| RAP forecast sounding, likely between Artesia and Roswell, courtesy of PivotalWeather |

Before heading to New Mexico that morning, my dad and Chuck and I took a self-guided tour of Texas Tech’s campus.

|

| A Husker, a Sooner/Husker, and a brief Husker touring Raiderland |

On our journey southwest from Lubbock, overcast skies gave way to mostly sunny conditions in southeast New Mexico, with stratocumulus developing overhead.

|

| Stratocumulus developing early afternoon, between Loco Hills and Maljamar, NM |

Our initial target was set for Artesia, NM. None of us had been to southeast New Mexico before, and we were unprepared for the constant scent of oil refineries and rattlesnake warning signs at the rest areas. We ate lunch and tossed a frisbee at Eagle Draw Park in Artesia. While throwing the frisbee, we noticed that the cumulus field was dissipating. Per a glance at visible satellite data, the cumulus field had shifted 20-30 miles to the north, towards Roswell. Thus, we took a leisurely drive to the north on US 285, and along the way caught up to the same chase vehicle that we saw at our hotels in Sidney, NE and Burlington, CO (see part 1). Roswell was much larger than I anticipated, and the countless aliens and flying saucers adorning business facades and porches were quite entertaining (my brother Carl and I like quirky roadside attractions).

|

| I'm not saying aliens, but ... |

|

| Aliens |

CI in our target area, basically in and just north of Roswell at this point due to the better moisture there, hadn’t occurred yet, though scattered supercells had formed in northern New Mexico near Philmont Scout Ranch and were moving southeast. Given the limited road network to our north and the near certainty of convective initiation in the Sacramento Mountains, we chose to stay put. We hung out just to the northwest of Roswell on the side of a gravel road, along with a tour group of other chasers who were already there. Finally, convection formed, seemingly on top of Capitan Peak (a relatively isolated higher mountain peak which evoked thoughts of Mount Erebor from Middle Earth (also referred to as The Lonely Mountain in The Hobbit)). This convection organized very slowly, eventually partitioning into multiple supercells as it drifted southeast out of the higher terrain.

|

| CI over The Lonely Mountain ... err, Capitan Peak |

|

| Strengthening/consolidating convection northwest of Roswell |

Supercell structure, in an environment with high cloud bases and a large amount of streamwise vorticity for southeast moving storms, became apparent once the storms moved southeast out of the mountains. We left our spot on the gravel road north of Roswell and headed south, bypassing the city to the west to avoid the numerous traffic lights along US 285. While in route, a suspicious lowering in the base of one of the trailing supercells formed, and there was a tornado report within approximately 10 minutes of when this series of photos was snapped (whether the reported tornado was associated with this lowering is difficult to say).

|

| Lead supercell and trailing supercell northwest of Roswell |

|

| Lowering, likely a wall cloud, possibly with tornado, under trailing supercell updraft |

We made it to a spot just east of the Roswell International Air Center, where many retired planes were being stored, providing one of the more eerie settings I’ve ever been in during a chase. The lead supercell’s updraft (hereafter just referred to as the supercell, as this became our target) acquired a twisted, corkscrew appearance. Impressive mammatus adorned the eastern part of the anvil above us. Finally, with the area in exceptional drought status, large amounts of topsoil were being lofted and ingested into the thunderstorm, causing a dust storm around us due to the powerful winds to the east-southeast of the mesocyclone.

|

| Supercell structure starting to take shape near Roswell International Air Center |

|

| Striations starting to form west of the airport, before the surface winds ramped up |

Dust from the inflow region (at least, that which didn’t get into our van, clothes, cameras, lungs, etc.) started to congregate under the mesocyclone (while the backlighting was difficult to deal with, this still made a neat timelapse).

|

| Dust party! at the supercell |

|

| Dust tracing the boundary layer flow near the mesocyclone |

|

| Chuck watching the Roswell supercell, getting ready to head south, dust storm underway |

We scooted southward on US 285 towards Artesia, trying to get well ahead of the storm for structure pictures (it had become clear that if a tornado were going to occur, there’d be too much dust to see it). We stopped several times to see mothership-like structure, though unfortunately we were driving between stops when the most impressive structure occurred.

|

| Supercell between Roswell and Artesia |

|

| Supercell and dust storm between Roswell and Artesia |

|

| Supercell and dust storm between Roswell and Artesia |

|

| Supercell and dust storm between Roswell and Artesia |

The supercell’s southeast movement brought it east of US 285, so we had to go into Artesia and head east on US 82 from there. By the time we got back ahead of the storm east of Artesia, it had become more outflow dominant. However, we had a beautiful vantage to watch the storm at sunset, and we were treated to a brilliantly colored display of laminar low-level storm features and cumulonimbus above a landscape of dark green brush and red dirt. We even got a brief sunset funnel cloud! Unfortunately, I had trouble capturing the vivid lighting, but the photos should give you some idea of what the scenery was like.

|

| Sunset shelf east of Artesia |

|

| Mammatus show east of Artesia |

|

| Sunset shelf east of Artesia |

|

| Updrafts at sunset east of Artesia |

|

| Sunset view east of Artesia |

|

| Sunset enchantment east of Artesia, NM |

|

| Small funnel cloud, if you can find it |

When the sunset waned, we decided to forego the following day’s severe weather setup near the Raton Mesa in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, in favor of taking advantage of 70 degree temperatures and overcast skies at Palo Duro Canyon State Park (TX). We headed to Hobbs, NM for the night, enjoying a great lightning display along the way before having to dodge street flooding in Hobbs. We missed a beautiful HP supercell and rain wrapped tornado near Campo, CO, as a result of the choice to hike, but got to enjoy pretty canyon scenery at Palo Duro instead. We were content with the storms we’d seen on the trip and were craving another hike before returning to Omaha.

|

| Hoodoo at Palo Duro Canyon State Park, near Amarillo, TX |